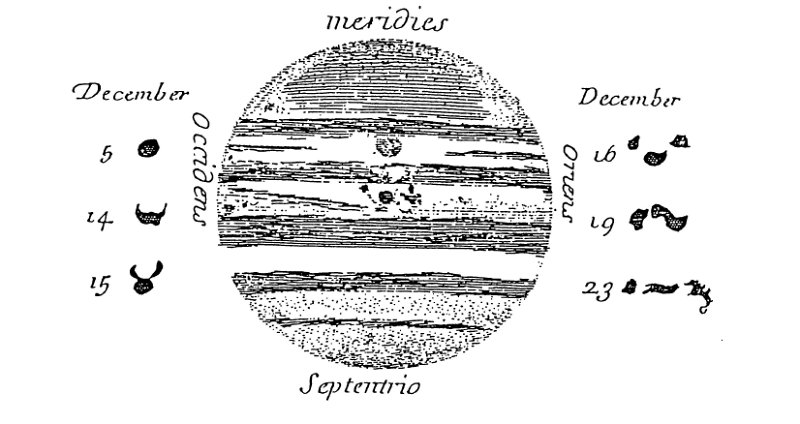

December 1690 sketch of new dark spot on Jupiter by G. D. Cassini and changes to the spot over 18 days

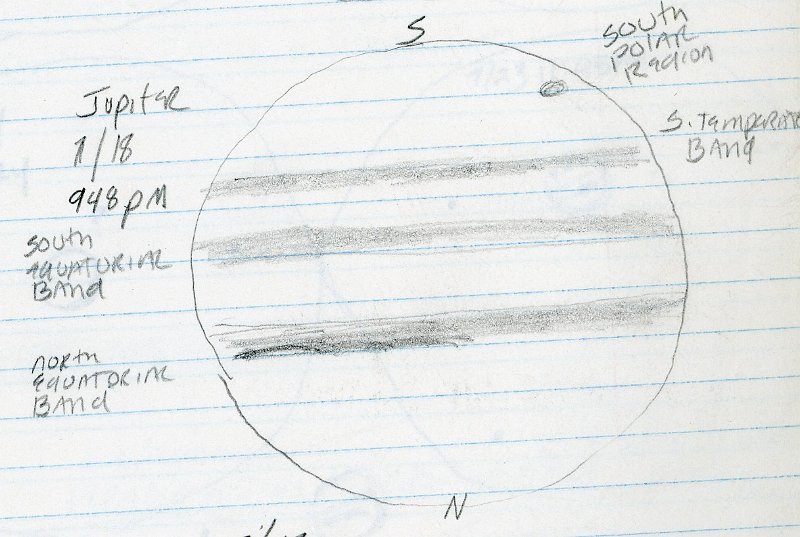

My July 26, 2009 sketch of the impact on Jupiter, discovered by Anthony Wesley (upper left 11-o'clock spot)

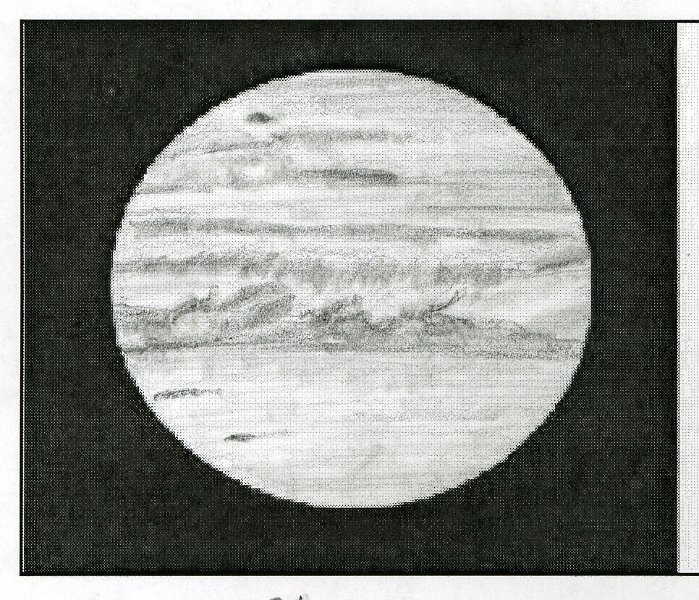

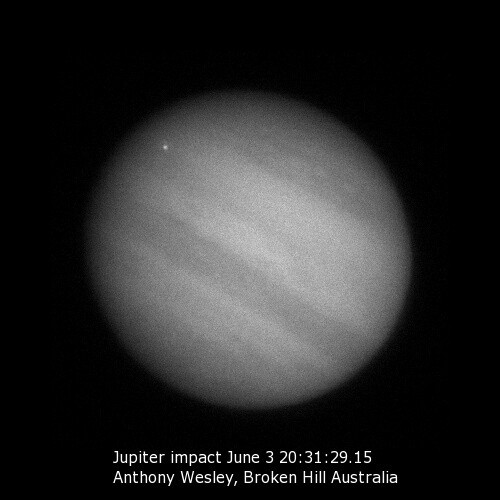

Anthony Wesley's preliminary (a raw frame from his video) showing new impact of Jupiter, June 3, 2010

On June 3, 2010, shortly before dawn in New South Wales, Australia, Anthony Wesley was imaging Jupiter. He saw a bright flash visually, and captured it on video. He quickly sent out an alert to imagers and scientists, followed soon with a preliminary raw frame from his video. Christopher Go also imaged this flash at the same time from the Philippines, and he also alerted the scientific and imaging communities.

The word spread like wildfire, and soon amateur and professional astronomers around the world were calculating when the impact area would rotate around the planet, to be hopefully visible from their own location, telescope or observatory. Would the impact leave a scar? No one knew for sure, but more observations were needed.

We’ve seen and documented three impacts to hit Jupiter since 1994 — but how many have we missed? Impact events leave no long-lasting scars on the surface of Jupiter. Jupiter’s bruises fade away.

Any science enthusiast who remembers 1994 will never forget the buildup to Shoemaker-Levy 9′s amazing impacts into Jupiter that summer. I have many sketches of what I observed visually those first nights when the world saw predicted cometary fragments hit Jupiter and leave visible impact scars. Astronomy clubs around the world saw increases in membership because of the press coverage.

I took my homemade 10-inch reflector telescope out on my back deck and observed and sketched Jupiter every clear night in the summer of 1994. I was, unwittingly at the time, continuing the tradition of citizen scientist recordings of visual astronomical observations — a tradition which goes back thousands of years.

Last year I was researching historical astronomical observations for my International Year of Astronomy (IYA) podcast series. I learned that Giovanni Domenico Cassini not only first saw Jupiter’s great red spot (called Jupiter’s permanent spot) in 1665, but he also observed and documented other large spots in December 1690.

Cassini’s sketched this feature over eighteen days in December 1690. His sketches show changes in the feature over time. His observations were published in 1792 as “Nouvelles descouvertes dans le globe de Jupiter.”

Today’s citizen scientists around the world observe their targets nearly every clear night. And when they see something unusual they immediately alert their community of colleagues. Sometimes, like in this case, other eyes or images confirm the observation. And when it is amazing enough, the world’s greatest eyes – Earth-based telescopes like Gemini, Keck, IRTF and even the orbiting Hubble Telescope — take aim.

Their eyes from Earth and space will make observations to delve deeper into Jupiter’s mysteries. Their data will complement observations of astronomy’s citizen scientists whose round-the clock and round-the-world nightly records are the eyes on the sky.

Ancient Astronomical Documents

Discovery of a Possible Impact SPOT on Jupiter Recorded in 1690

The Shoemaker-Levy 9 Spots on Jupiter: Their Place in History

There was a big study in 1994 on whether there are SL-9-style impact spots in historical drawings – with a clear NO as an answer. That paper’s author just told me he stands by his conclusions which (AFAIK) are shared by other experts in old Jupiter drawings: Jupiter’s atmosphere makes its own dark streaks that come and go.

Thanks, I’ll adjust my writeup and include both studies. Jane