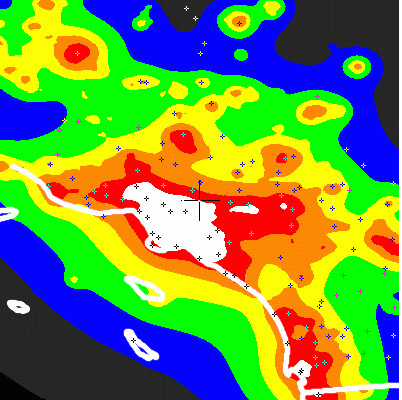

The white area is greater Los Angeles. I observed from my driveway in Monrovia, indicated at the "red/white" border zone marked with cross-hairs

My meteor watching setup - comfortable chair, blanket, clipboard, red flashlights, clock, binoculars, snacks

The graph shows the ZHR (Zenithal Hourly Rate), which is the number of meteors an observer would see under a very dark sky with the radiant of the shower overhead. (this chart is being updated as more reports are submitted)

I prefer to drive far from LA to view meteor showers from a dark sky, but those darn showers don’t always happen on weekends or days I can take off work. So this week, I observed the Quadrantid Meteor Shower from my bright moonlit Los Angeles County driveway until after midnight, snoozed until moonset at 3:00 a.m., then had a fairly decent sky from 3:00 a.m. to 5:15 a.m. when the sky started to brighten from the dawn light. Although I didn’t see many meteors, and only one before the moon set at 3:00 a.m. PST January 4th, I was thrilled with my observations.

Take a look at this colorful map. See that white blob? That’s Los Angeles on a light pollution map. That white ribbon? That’s the California coastline. White on these maps designates the most light polluted areas in the world. There is no worse place for light pollution. LA is the model of a major metropolitan meteor-observing maelstrom of star-obscuring light pollution. This white color on the map is described in bleak terms on the Clear Sky Chart website’s light pollution map page: “The entire sky is grayish or brighter. Familiar constellations are missing stars. Fainter constellations are absent. Less than 20 stars visible over 30 degrees elevation in brighter areas. Limiting magnitude ranges from 3 to 4. Most people don’t look up.” Monrovia is on the north edge of the white blob that is Los Angeles, indicated by the cross-hair. (all those little crosses on the map are other astronomy locations). Red is the next to worst light pollution zone, and the ribbon of red color next to Los Angeles is the San Gabriel Mountain foothills. Monrovia is nestled between the Los Angeles basin and the mountains. It’s fine for moon and planets at our monthly Old Town Sidewalk Astronomy nights, not so good for meteors and anything else astronomical.

The three oval white blobs on the left lower quadrant are Santa Catalina, San Clemente and San Nicholas Islands! The yellow, green and blue zones are in the ocean. It’s even light polluted well off the coast of Southern California!

I usually drive 150-300 miles to one of the black teardrop shaped pin spots on this light pollution map of California. Those are the best and darkest locations for the stargazing and astrophotography we enjoy. Mojo and I prefer Amboy Crater, Hole-In-the-Wall Campground in Mojave National Preserve, and a spot near Desert Center 60 miles past Indio on I-10. We also love the dark skies at Glacier Point at Yosemite.

But this week was the peak of the Quadrantids, and I didn’t want to drive a 6-hour round trip for 3 hours of meteor watching, especially on a work night. So I found a good spot in my driveway and it blocked a lot of the local light sources. I nestled my comfy observing chair up next to a cinder block wall. This wall, plus strategically placed tall trees blocked the moonlight and oncoming car lights from my view. To my south was not the Milky Way, but the milky gray — the color of skies over Los Angeles. I could see the big dipper stars, and part of the little dipper. Below these two constellations was the radiant of the Quadrantids. This area wouldn’t even rise until after midnight, but I wanted to say I observed the Quadrantids during the actual peak, and check for earthgrazing meteors on the horizon.

I estimated my limiting magnitude at a dismal 3.9 using star counting charts. I settled into my meteor-watching chair, sipped some hot green tea and waited. And waited. And waited some more. From 11:00 p.m. until 12:30 p.m (PST) I saw exactly one meteor, and it wasn’t even a Quadrantid. The moon was high overhead now, and so I snoozed until moonset at 3:00 a.m. Wednesday morning.

When my alarm went off, I headed back out to the driveway. I adjusted my chair, adjusted the dark blankets I placed over the fence between my driveway and the neighbor’s all-night security lights. By careful placement of my head, and with blankets on the fences and shrubs I had no lights shining directly at me.

It was a little after 3 a.m. and I started observing an area above the radiant, centered on the bowl of the big dipper. My back was facing the well-lit LA basin, my view to the north was overlooking the San Gabriel mountains and Mt. Wilson Observatory. By 3:18 I had seen my first Quadrantid. At 3:30 I counted stars again. Without the moonlight, my limiting magnitude rose to a respectable 5.1 using this star counting chart. I repeated this exercise several times, until I could barely see stars after 5:00 a.m. My last limiting magnitude calculation before I packed it in was 2.9.

This chart shows the data from 48 observers in twenty countries. Data (still coming in, I’ll update the chart a couple of times) is averaged based on the observers seeing conditions, visual acuity, cloud cover percentage, etc. You can see that the highest rates — at the peak of the Quadrantids were in excess of 80 per hour. This is the number of meteors which would be seen overhead at the zenith (in a dark sky) if the highest rate was kept steady for one hour. In reality, the highest rates last usually for only a few minutes for showers like the Quadrantids with a very narrow peak. How many did I see from my Monrovia driveway? I saw three from 3:00-3:30 a.m. and another three from 3:30-4:00 a.m. I saw five from 4:00 to 4:30 a.m. and between 4:30 and 5:00 a.m. I saw three, plus heard nearby roosters crowing! I finished the observing with 2 more Quadrantids between 5:00 and 5:15 a.m. and was heralded by a veritable rooster symphony as the sky brightened. My total count over a little more than 2 hours was 16 lovely Quadrantids, two sporadics, and one Anthelion! Here’s my report which I submitted to the International Meteor Organization. Amazingly, this number is almost exactly the prediction from NASA’s Meteor Fluxtimator when I entered Quadrantids from downtown Los Angeles on the 3rd and 4th of January 2012. How about that! You can observe a meteor shower from Los Angeles!

Here’s the meteor shower calendar for 2012

Interested in counting meteors? Here’s the IMO Visual meteor observing form plus instructions and FAQs

More about the Quadrantids and their namesake constellation, Quadrans Muralis

Nicely detailed report Jane!

Thanks!

Saw an amazing one at around 9pm on Dec 30th to the west, from here on Monrovia/Arcadia border (just taking dog out for a walk). When I got back I checked out to see if anyone else had seen it on Twitter and found some sightings that could’ve been the same one (some tweets at http://www.twitter.com/peterbennettdot ). Seemed about 10x bigger than any metor/shooting star I’ve ever seen and I also I recall seeing a round ‘meteor’ shape at the front.

Best,

Peter

[...] Viewing meteor showers from light polluted LA – not impossible! [...]

[...] Viewing meteor showers from LA not impossible. [...]